Constitutional Review Series: Republic of China (Taiwan)

Glenn E. Chappell

Originally published on June 19, 2022

One of Asia’s freest countries is not even a country at all—at least according to the world diplomatic community. Yet regardless of its formal status, no one can deny that the Republic of China, or Taiwan, is an important actor on the world stage. In a single generation, Taiwan evolved from a totalitarian land under perpetual martial law to a thriving democracy with forward-looking heads of state and lawmakers and a bold, empowered judiciary. The world marveled as this island nation of 23 million people peacefully and rapidly transformed in nearly all societal respects—political, economic, and cultural.

Taiwan’s Constitution laid the legal groundwork for Taiwan’s fast-track journey to democracy. Although most of it was drafted by an authoritarian, unchallenged political party then ruling the island by fiat, this charter contains all the ingredients of a strong constitutional foundation for rights-based governance. Indeed, Taiwan’s Constitution contains the checks and balances, sweeping protections for individual rights, and substantive consistency lacking in the charters of other countries that embraced constitutionalism much earlier.

In this installment of our review of the world’s constitutions, we’ll examine how a unique conjunction of public pressure, principled political leadership, and bold judicial decision making breathed life into Taiwan’s majestic fundamental law and enabled it to achieve much of its grand potential.

Taiwan’s Constitutional Journey

One can’t understand the story of Taiwan’s Constitution without understanding the larger history of Taiwan. Until the end of World War II, Taiwan was under Japanese colonial rule. When the war ended and Japan surrendered to the United States, Taiwan came under the governance of mainland China, which at that time was governed by a republican regime. Just a few years later, Communist forces under Mao Zedong prevailed over the republican forces, led by Chiang Kai-Shek, and drove them off the mainland. In 1949, the republican government, military, and more than a million citizens fled the mainland and settled on Taiwan, with the old republican government maintaining dominion over Taiwan even as the Communist forces consolidated their control over the mainland.[i]

The republican government in exile, controlled by Chiang Kai-Shek’s Kuomintang party, evolved into Taiwan’s current government. Today, the Communist government of mainland China refuses to recognize the government of Taiwan. Conversely, Taiwan asserts that its government is the rightful government of all China, including Taiwan and the mainland.[ii] Only a tiny handful of countries recognize Taiwan as an independent state, and even Taiwan itself has not declared itself as such.[iii]

During the years of Japanese control, the Meiji Constitution—the fundamental law of Japan and “the first modern written constitution in East Asia”—was officially in force in Taiwan, but this was more true on paper than in practice.[iv] At the same time, the Republic of China on the mainland—which, again, would later become Taiwan’s government—was developing its own constitutional system. Working at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, its representatives drafted the Republic's first provisional charter in 1912.

The Republic of China's Constitutional Drafting Committee at the Temple of Heaven in 1912. That year, the Committee drafted the nation's first provisional constitution.

Rowanwindwhistler, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>,

via Wikimedia Commons

Photo taken by the author on the same spot 107 years later

In 1931, after Chiang Kai-Shek and his Kuomintang party took over, the government published a new provisional constitution that setup a one-party system.[v] Then, in 1946, it drafted a constitution with five branches of government and a democratic system. The government intended this third constitution to be the permanent one. It went into effect in 1947.[vi]

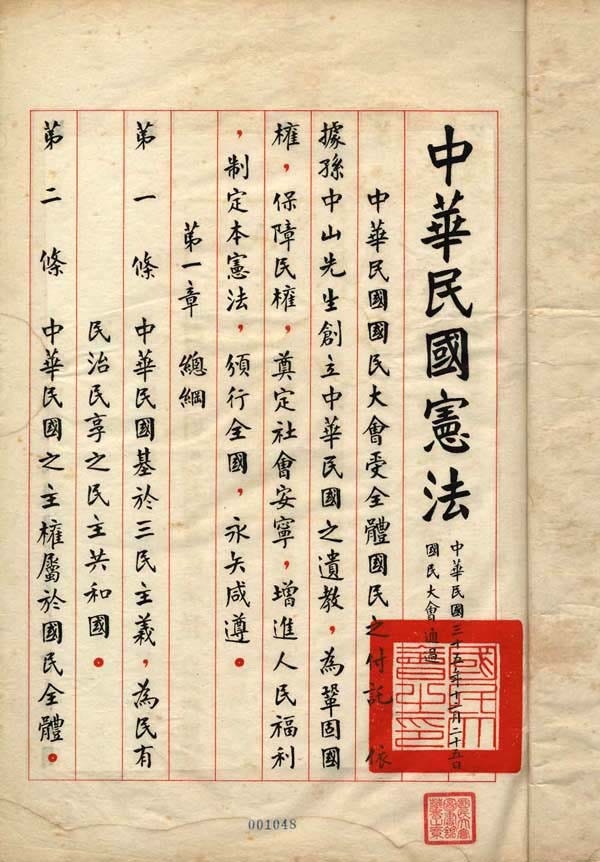

First page of the 1947 Constitution

When the republican government of China fled to Taiwan in 1949, the Constitution of 1947 remained in effect on the islands of Taiwan under republican control. But the government maintained a state of martial law in Taiwan for the next 38 years, until 1987.[vii] During these decades, the government wrote into the Constitution so-called “Temporary Provisions,” measures of questionable legality that practically suspended the Constitution, restricting opposition to the governing party, tightly controlling the press, preventing democratic elections, and allowing the president to rule by decree without permission by the legislature.[viii]

In 1987, President Chiang Ching-kuo finally ended martial law, taking a crucial step toward democratic reform. One year later, President Lee Teng-hui rose to power. During his twelve-year presidency, Lee, nicknamed “Mr. Democracy,” guided Taiwan through a time of transition to democracy.[ix] Although he rose to the presidency and began his tenure without public input, he would, in 1996, become the first president directly elected by the people in a free, contested election.[x]

President Lee Teng-Hui, "Mr. Democracy"

中華民國總統府(國史館提供), CC BY-SA 4.0, <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>

One of Lee’s boldest and most important steps was lifting the Temporary Provisions in 1991, a “watershed” in Taiwan’s history.[xi] Abolition of the Temporary Provisions fully restored the primacy of the 1947 Constitution and eliminated the legal basis for the government’s disregard of it. This development, along with Lee’s many other democratic reforms, made possible a first in Taiwan’s history: the peaceful election in 2001 of a president from a political party other than the Kuomintang, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).[xii]

During Taiwan’s years-long reform process under Lee and subsequent presidents, the now-restored Constitution of 1947 began to play a larger role, courts started enforcing it (sometimes aggressively so), and the government began to respect it.[xiii] During these transition years, Taiwan amended the Constitution a number of times. The most sweeping changes occurred in 2005, when a series of amendments called the Additional Articles were ratified. These Articles transformed Taiwan’s government from a parliament-focused system to a hybrid system with a directly elected president, eliminated a three-house parliamentary system in favor of a unitary system, reformed the judiciary, and adjusted the division of powers between the central government and local authorities.[xiv]

The current Constitution of Taiwan is the product of this history and the numerous constitutional reforms that tracked it. In keeping with Taiwan’s position that the Republic of China is the rightful government of all China and that the ultimate goal is to re-unify with the mainland after it is liberated from Communist rule, the Constitution refers to itself as governing the “free area of the Republic of China” and describes itself as meeting the needs of Taiwan’s citizens “prior to national unification.”[xv]

Two Documents, One Constitution

The Constitution establishes a democratic republic, “governed by the people, and for the people,” that vests sovereignty in “the whole body of citizens.”[xvi] It’s divided into fourteen chapters and 186 articles (this includes 174 articles in the original 1947 Constitution and 12 in the Additional Articles). It begins with a few general provisions, moves to provisions establishing individual rights and duties, then to chapters setting out the powers and limitations on Taiwan’s four branches of government and local governments, then to the election system, and then to the process for amending and enforcing the Constitution.

In official publications of the Constitution, the Additional Articles are included at the end of the 1947 articles (several of which have also been amended over the years) and titled separately. These twelve articles have their own preamble and are separately numbered from those in the 1947 Constitution.

The Preamble to the 1947 Constitution states that the Constitution’s goals are to “consolidate the authority of the State, safeguard the rights of the people, ensure social tranquility, and promote the welfare of the people.”[xvii] The Preamble to the Additional Articles states that the new amendments are designed “[t]o meet the requisites of the nation prior to national unification.”[xviii]

Individual Rights and Duties

The Constitution’s provisions on individual rights are succinct and less comprehensive than those in the Eastern European constitutions we’ve previously explored. For example, the Constitution of Ukraine and the Constitution of the Russian Federation each include 48 articles in their chapters dedicated to individual rights and duties, and they discuss and protect individual rights in many other provisions sprinkled throughout other chapters. By contrast, Taiwan’s Constitution contains only eighteen articles in its chapter on individual rights and duties, and it rarely discusses additional rights in its other chapters, which are largely focused on government structure and authority. Nevertheless, the protections for individual rights in Taiwan’s Constitution are still robust because of their sweeping scope. The basic rights and freedoms recognized in Taiwan’s Constitution can be grouped loosely as follows:

Equality

A guarantee of “complete equality among the various ethnic groups in the Republic of China”[xix]

Equality before the law regardless of sex, religion, ethnic origin, social status, or political party

A requirement that the government guarantee “[p]ersonal freedom” to the people[xx]

Required government protection of the dignity and personal safety of women, elimination of sexual discrimination, and support for gender equality

The right to guaranteed, government-provided support for the physically and mentally disabled, including insurance, medical care, obstacle-free environments, education and training, vocational guidance, support and assistance in everyday life, and support and assistance in developing and attaining personal independence

Requirement that the government affirm cultural pluralism and actively preserve and foster the development of aboriginal languages and cultures

Requirement that the government safeguard and ensure political participation of aboriginal peoples

Guaranteed assistance and encouragement for aboriginal education, culture, transportation, water conservation, health and medical care, economic activity, land, and social welfare

The right to political participation by citizens living overseas

Protections for the Criminally Accused

Prohibition on arrest or detention other than by an organ of the judiciary or the police, unless a person is caught in the act of actively committing a crime (and then, only as prescribed by law)

Prohibition on trial or punishment other than by a court of law and in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law and the right to resist such trial or punishment

Requirement that a person accused of a crime and any relative or friend they designate be promptly informed in writing of the charge

Absolute requirement that the police turn over a person accused of a crime to pre-trial judicial custody within 24 hours of arrest or detention

The right to petition a court for an investigation into the legality of an arrest or detention, and the requirement that the court investigate and act on the petition within 24 hours

Prohibition of trial be military tribunal for any person other than a person on active military duty

Public Health and Welfare

Required government support for universal health insurance

Required government support for research into both modern and traditional medicines

Required government support for, and emphasis on, social welfare and insurance, employment, medical and health care, with a constitutionally required priority placed on funding social relief and assistance and employment initiatives for citizens

Constitutionally required priority placed on funding education, science, and culture

Personal Autonomy

Freedom of residence and change of residence

Freedom of “privacy of correspondence”[xxi]

The “right to existence”[xxii]

The right to work

The right to own property

Required government protection of and support for small and medium-sized businesses

Expressive Freedoms

Freedom of the press

Freedom of speech, teaching, writing, and publication

Freedom of religious belief

Freedom of assembly and association

The right to petition the government, lodge complaints, and institute legal proceedings

Political Power

The “right of election, recall, initiative, and referendum”[xxiii]

The right to take public examinations and hold public office

In an impressive confirmation of individual liberty, Article 22 also provides that “[a]ll other freedoms and rights of the people that are not detrimental to social order or public welfare shall be guaranteed under the Constitution.” This is extraordinary: While we previously saw that the United States Constitution and the Constitution of the Russian Federation both have clauses contemplating recognition of other rights not specifically recognized in those documents, it is rare to see a constitution affirmatively protect and constitutionalize all freedoms and rights not detrimental to public welfare. To be clear, the practical effect of this provision is questionable because the terms “social order” and “public welfare” are ambiguous and malleable to suit government ends. But this provision is still impressive because it sets up a clear presumption in favor of individual liberty—a presumption that gives courts important interpretive guidance when construing and enforcing the Constitution’s other individual freedoms.

The Constitution also recognizes that these rights are not absolute. Article 23 provides that the rights and freedoms it protects “shall not be restricted by law except such as may be necessary to prevent infringement upon the freedoms of others, to avert an imminent danger, to maintain social order, or to promote public welfare.”

Taiwan’s Constitution also imposes the following affirmative responsibilities on citizens: the duty to pay taxes and serve in the military as required by law, and the “right and the duty to receive elementary education.”[xxiv]

Structure of Government and Separation of Powers

Next, the Constitution establishes the framework of Taiwan’s government. The central government is made up of five branches—the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Examination Yuan, and Control Yuan—with a president serving as head of state.

The Constitution also recognizes and guarantees the independence and authority of provincial and local governments in certain matters. Specifically, the Constitution gives the central government authority over a wide range of enumerated areas of law, including foreign affairs and trade, national defense, immigration, criminal, civil, and commercial law, aviation, highways, railways, and postal and telecommunication services, state-owned enterprises, the currency system and State banks, weights and measures, the education system, shipping and deep-sea fishery, public utilities, eminent domain, census, public health, and labor and other social legislation. However, the central government may delegate its authority over many of these matters to provincial or local government if it so chooses. The provincial governments have constitutional authority over areas such as administration of provincial cities and public health, education, cooperative provincial enterprises, provincial natural resources, and provincial debts, banks, agriculture, police, charitable, and public welfare works. The counties enjoy similar authority over the same county-level institutions and projects.

For any areas of law not specifically enumerated in the Constitution, the charter provides that those areas fall to the central government if they are “national in nature,” to the provinces if they are “provincial in nature,” and to the counties if they “concern[] the County.”[xxv] For these unenumerated areas, the Legislative Yuan settles any jurisdictional disputes between the central, provincial, and county governments.

The presidency. Taiwan’s Constitution makes the president head of state. The president is responsible for representing the nation in foreign relations, and they are the supreme commander of the military. The president and their backup, the vice president, are directly elected by the populace, with the candidate receiving the most votes elected.

The president and vice president must be at least 40 years old. They run and are voted on together on the same ticket, are elected to four-year terms, and may not serve more than two consecutive terms. The president and vice president enjoy immunity from prosecution, except for rebellion or treason, unless they have been recalled or relieved of their duties.

Taiwan’s president has many powers under the Constitution, but they are carefully circumscribed. The president may declare martial law, but only with the approval or subsequent confirmation of the Legislative Yuan. The president may also issue emergency orders and take other actions needed to deal with natural disasters, epidemics, or financial or economic crisis when the Legislative Yuan is in recess, but the Executive Yuan must assent, and the emergency measures must be submitted to the Legislative Yuan for confirmation within one month. If the Legislative Yuan rejects the measures, they cease to be valid.

Taiwan's current president, Tsai Ing-wen

glen photo/Shutterstock.com

The president may also issue pardons, commute sentences, grant amnesty, and restore civil rights for the convicted.

The Executive Yuan. The Constitution establishes the Executive Yuan as the executive branch of Taiwan’s government, which oversees the day-to-day operations of the government and administrative state. The Executive Yuan is comprised of a premier, vice premier, cabinet of ministers, chairs of government commissions, and other at-large ministers. The president appoints the premier—who leads the Executive Yuan—without the need for confirmation by the Legislative Yuan. The rest of the positions, including the vice president, are appointed by the president upon recommendation by the premier (also without legislative approval). The Constitution vests the Executive Yuan with the right and duty to submit a budgetary bill to the legislature each year (a perhaps overlooked but important power—the right to fix the terms of the debate regarding the budget and drive government spending priorities). Moreover, the Legislative Yuan is prohibited from increasing the budget submitted by the Executive Yuan; it may only cut spending.

The Legislative Yuan. Taiwan’s legislature consists of just one house (the proper name for this is “unicameral”), and its members are directly elected to four-year terms. The Legislative Yuan elects its own president and vice president (sometimes translated in English as a “speaker” and “deputy speaker”) by majority vote at the beginning of each new four-year legislative term, and those leaders serve until the end of the term unless impeached by a majority vote and then removed by a two-thirds vote of legislators.

Assembly hall of the Legislative Yuan

TimeDepot.twn/Shutterstock.com

The Judicial Yuan. The Republic of China’s judiciary has constitutional authority to try criminal, civil, and administrative-law cases. It also has authority to impose disciplinary sanctions on public employees. In addition, the Judicial Yuan has the final say on interpretation of the Constitution and laws.

The Judicial Yuan consists of 15 grand justices, who are nominated by the president of the Republic and confirmed by the Legislative Yuan. A president and vice president—chosen by the grand justices—preside over the Judicial Yuan. Each grand justice serves an eight-year term and may not serve more than one term consecutively. However, the justices chosen as president and vice president do not enjoy the guarantee of an eight-year term with respect to those offices.

Current grand justices of the Judicial Yuan in the courtroom where they sit to form the Constitutional Court

Credit: Judicial Yuan, https://www2.judicial.gov.tw/FYDownload/en/p01_03.asp

Aside from establishing powers of the grand justices, the Constitution does not set out the structure of Taiwan’s court system. Thus, the system is established by statute and includes a series of trial, appellate, and administrative courts at national, municipal, and district levels.[xxvi] Under that system, the Supreme Court is the court of last resort for civil and criminal cases, except for appeals of constitutional decisions.[xxvii]

The grand justices of the Judicial Yuan make up the highest judicial body in Taiwan, and they have the power to authoritatively interpret the Constitution and statutes. When tasked with interpreting the Constitution, the 15 grand justices form and sit on a Constitutional Court, which hears cases and arguments according to procedures outlined by statute and is presided over by the president of the Judicial Yuan. The grand justices hear petitions by members of the central or local governments of the Legislative Yuan to perform abstract (non-adversary) review of the constitutionality of laws or interpret constitutional provisions, petitions by lower courts to strike down laws the lower courts must apply in pending cases and which the lower courts believe are unconstitutional, disputes between different bodies of government over their respective constitutional competencies, and last-resort petitions by individuals who assert their constitutional rights have been violated and have exhausted all other judicial remedies.

When necessary, the grand justices also form a counsel to review the impeachment of a president or vice president of the Republic and decide whether to dissolve “unconstitutional political parties.”[xxviii] The Constitution defines a political party as “unconstitutional” if its “goals or activities endanger the existence of the Republic of China or the nation’s free and democratic constitutional order.”[xxix]

The Judicial Yuan submits its own budgets to the Executive Yuan to be included in the annual budget bill, and the Executive Yuan may not reduce or exclude the Judicial Yuan’s proposed budget from its submission to the legislature.

The Examination Yuan. The Examination Yuan is Taiwan’s civil service commission. It oversees the qualification, hiring, promotion and transfer, supervision, and discipline of civil servants (non-politically appointed career government employees) and determines their salary scales and benefits programs. The Examination Yuan is headed by president and vice president, who are chosen and serve terms according to statutory law.

The Constitution requires the Examination Yuan to select public employees through an open, competitive examination process and to remain non-partisan. Additionally, the Constitution gives the Examination Yuan authority to submit bills within its provenance to the legislature.

The Control Yuan. The Control yuan is the final branch of the Republic’s government. It is an independent body vested with auditing, impeachment, and censure power. It is made up of 29 members, each of which is nominated by the president of the Republic and confirmed by the legislature. All members of the Control Yuan serve six-year terms. The Constitution requires each member of the Control Yuan to have no political party affiliation and to exercise their authority independently. They are also prohibited from holding any other public office or engaging in another profession.

The Control Yuan is responsible for auditing the annual budget each year. It also may impeach any member of the central or local governments, other than the president or vice president of the Republic. This includes judges or justices of the Judicial Yuan or functionaries in the Examination Yuan. An impeachment of these officials may be initiated by any two or more members of the Control Yuan, and after investigation, voted upon by a quorum of at least nine members. If the impeachment is approved, it is sent to a special court of the Judicial Yuan to be tried on the merits. And it may censure government officials.

Checks and Balances

Taiwan’s Constitution is filled with mechanisms designed to be used by each branch to prevent overreach by the other branches.

First, consider removal, recall, and impeachment. If the Legislative Yuan passes a no-confidence vote against a premier by a simple majority, the premier must step down. But if the president disapproves of this action, he may dissolve the Legislative Yuan and hold a special election to replace the legislature. But the legislature may, by a two-thirds majority, initiate a recall of the president or vice president. If the recall passes the legislature, it goes to the people, who can remove the president or vice president with majority vote. The Legislative Yuan also holds the power to impeach the president or vice president in lieu of recall. The legislature may commence an impeachment with a simple majority, and a two-thirds majority is required for removal. If the legislature has enough votes to remove the president or vice president, it submits the case to the grand justices of the Judicial Yuan, who review the impeachment and uphold or reject its legality. If the Judicial Yuan upholds the impeachment, the president or vice president is removed.

Supervision is another way in which the branches control one another. The Legislative Yuan supervises the executive branch in two ways. First, its members have the right to question the premier or the ministers and chairmen of commissions of the Executive Yuan. Second, if the Legislative Yuan doesn’t agree with a major policy of the administration, it may pass a resolution requesting the Executive Yuan to change the policy. When it receives such a resolution, the Executive Yuan may request that the legislature reconsider the resolution, but only if the president of the Republic agrees with the Executive Yuan. If the Executive Yuan requests reconsideration of a resolution, the Legislative Yuan may overrule the request by a two-thirds vote. If the legislature passes such an override, the premier must obey the legislature’s resolution or resign from office. On the other side of the ledger, the Executive Yuan may also check the Legislative Yuan’s authority using a similar process. If the Executive Yuan finds a statute, budget, or treaty passed by the legislature difficult to enforce and the president agrees, the Executive Yuan may file a request for reconsideration within ten days of the enactment’s passage. The Legislative Yuan can overrule this request, but it can only do so with a two-thirds majority. Although the president of the Republic of Taiwan doesn’t enjoy veto power like presidents in many other countries, the president can use this mechanism to work in concert with the Executive Yuan to check the legislature’s actions.

Immunity is also an important check on aggrandizement by certain branches. Members of the Legislative Yuan and Control Yuan enjoy immunity from any opinions expressed or votes cast in the course of their duties, and they may not be arrested or detained for any reason without the permission of the full bodies in which they serve, unless caught in the act of committing a crime. And unless impeached or recalled, the president may not be prosecuted for crimes other than rebellion or treason.

The judiciary also enjoys robust protections. The Constitution requires judges to be impartial and try cases in accordance with law and independent of outside interference. Further, judges (other than the grand justices of the Judicial Yuan) receive lifetime appointments, and they may not be removed unless they have been found guilty of a crime, subjected to a disciplinary act, or declared incompetent to serve. And the Constitution prohibits suspension or transfer of a judge or reduction of a judge’s salary except by legislative act.

Finally, the Constitution’s limits on the power of the purse are powerful checks: only the legislature may approve budgets, but only the executive can submit budgets, and the legislature can’t increase the proposed budget (it can only reduce it). And the executive can’t change or disregard the budget submitted by the judiciary in its submission to the legislature.

The Amendment Process

Taiwan’s Constitution may be amended through only one four-step process set forth in the Additional Articles. First, an amendment receives a legislative vote if at least one-fourth of the members of the Legislative Yuan propose it. Second, the amendment passes if at least three-fourths of legislators vote for it (and at least three-fourths of the legislature must participate in the vote). Third, the amendment is announced to the public and a six-month public comment period takes place. Fourth, the populace votes on the amendment in a referendum, and the amendment passes if at least one-half of the total number of “electors” vote in favor of it.[xxx] (In other words, the proposed amendment must receive enough “yes” votes that those votes equal at least one-half of the total number of votes cast in the previous presidential election.)

Constitutionalism in the Republic of China

Taiwan has a developed a strong commitment to constitutionalism. Recall that although Taiwan’s Constitution in theory went into effect in 1947, the government did not even claim to enforce or respect large parts of it until forty years later, when martial law was lifted in 1987 and the Temporary Provisions were abolished in 1991. But in this short time, Taiwan has soared to the top of the rankings on democracy, freedom, and constitutionalism. In 2022, Freedom House ranked Taiwan 19th in the world in its Freedom in the World Index, with a score of 94 out of 100 points (11 points higher than the United States).[xxxi] In its 2021 Human Freedom Index, Cato Institute ranked Taiwan as the 19th freest place in the world.[xxxii] Both organizations give Taiwan strong rankings in the areas of freedom of speech, religion, expression, and the press, democracy, minority rights, and the rule of law.[xxxiii]

As to the judiciary, Taiwan’s Constitutional Court is independent and strong. During the martial law era, the Judicial Yuan was weak and dominated by the central government. According to one scholar, the grand justices were “cautious,” and the Court at times could even “be seen as an instrument of the KMT regime.”[xxxiv] But the reforms presided over by President Lee empowered the judiciary and emboldened the Judicial Yuan to enforce the country’s charter.

Indeed, the Court did not just benefit from these democratic reforms; its bold decisions drove this evolution. In June 1990, the Court handed down what is considered its most important constitutional decision. It ruled that members of the legislative branch that had been elected in 1948 on the mainland and sat without challenge during the martial law years could not continue to hold power without an election.[xxxv] Under the version of the Constitution in effect at the time, the house these authoritarian-leaning members served in and dominated (the National Assembly) held the sole power to amend the Constitution, and these legislators had the political power to band together to stymie other reform efforts in the legislature (the 2005 Additional Articles modified the constitutional amendment process and did away with the National Assembly, consolidating the legislative branch into one house). This decision precipitated the election of a new generation of legislators chosen by the people, forced these officials to retire, and removed a massive roadblock to democratic reform. Tom Ginsburg, a scholar of Asian constitutionalism, writes: “Without this decision of the Grand Justices, the democratization process would have remained at a standstill, with the possible consequence that then-President Lee Teng-hui would never have cultivated his strong position within the KMT, and reform would have been delayed indefinitely.”[xxxvi]

In another crucial decision, the Court invalidated constitutional amendments by the National Assembly that followed a ratification process rife with procedural irregularities and which the Court determined would conflict with existing constitutional provisions and undermine “the essential nature of the Constitution” and the “constitutional normative order.”[xxxvii] And in yet another, the Court enforced separation of powers by ruling that all the nation’s courts must be organizationally placed under the authority of the Judicial Yuan and therefore invalidating laws organizing certain courts as departments of the Executive Yuan.[xxxviii] In all these decisions, the Judicial Yuan aggressively enforced the separation of powers, democratic accountability, and core values enshrined in the nation’s charter.

In addition to these critical structural decisions, the Constitutional Court’s decisions on expressive freedoms, individual liberty, and due process were both made possible by and drove Lee’s democratic reforms. As just a few examples, the Court:

Struck down a prospective ban on political rallies in support of communism and secessionism as an unconstitutional prior restraint of free association and speech[xxxix];

Invalidated prior restraints on both assembly and commercial advertising[xl];

Forced “a complete revision” of Taiwan’s Criminal Procedure Code to bring it into line with “international norms”[xli];

Struck down a law mandating fingerprinting as a condition of receiving an identification card as a violation of the right of privacy[xlii];

Required the government to pay just compensation when asserting a public easement over private roads or installing pipelines and other infrastructure under private roads or lands[xliii];

Set boundaries on government infringement on the right to work by upholding certain laws banning persons convicted of serious crimes from working as taxi drivers but striking down other laws suspending persons from working as taxi drivers when convicted of more minor offenses, where it was not shown that those drivers presented a danger to riders[xliv];

Struck down laws defining marriage solely as the union between a man and a woman, making Taiwan the first nation in Asia to recognize same-sex marriage.[xlv]

One of the first couples to register their marriage on May 24, 2019, the day Taiwan became the first Asian nation to legalize same-sex marriage when the Legislative Yuan implemented the Constitutional Court's decision

Q Wang/Shutterstock.com

As to individual rights, the Constitutional Court’s same-sex marriage ruling is illustrative of the Court’s power and the government’s and the people’s acceptance of its rulings. When the United States Supreme Court struck down state same-sex marriage bans in 2015, support for gay marriage neared 60% in public opinion polls.[xlvi] Not so in Taiwan. There, in 2018—a year after the Constitutional Court issued its decision—less than 40% of the public supported the right of same-sex couples to marry.[xlvii] Indeed, in a fit of backlash, voters approved a series of anti-LGBT referenda in 2018. Nevertheless, the Legislative Yuan complied with the Court’s order requiring it to pass legislation legally recognizing same-sex marriage and providing same-sex couples with the same legal rights as straight couples.[xlviii]

Author’s Reflections: A Team Approach to Democratization

In prior articles, we’ve focused on nations that have struggled to transition from authoritarian states to constitutional democracies. But in this article, we’ve seen that Taiwan made this shift comparatively quickly and successfully. How come? The answer is complicated, but in my view it’s attributable to a series of concurrent and overlapping factors.

First, Taiwan was led by a president deeply committed to constitutionalism and democracy. President Lee, or “Mr. Democracy” as he was called, boldly led the way in reforming Taiwan’s government. The power of political leaders to influence the masses—for better or worse—is a thread running tightly throughout human history. Kings, presidents, and other popular figures have started or ended movements, changed public attitudes, and altered the fortunes of their nations’ history in ways that no one could have foreseen right up until these events happened. The same is true in Taiwan. While public pressure for democratic reforms clearly pushed Lee (see below), he could have endorsed these reforms halfheartedly or in a much more incremental fashion. We’ve seen movements for reform grow stronger and then peter out gradually or even quickly when political leadership doesn’t fully embrace the public’s demands. Lee, an imperfect leader just like anyone else, deserves enormous credit for his even-keeled implementation of measures that, while they might have increased his popularity, indisputably reduced his own power. Political leadership matters; it always has and always will.

Second, the Judicial Yuan courageously supported Lee’s efforts by enforcing the separation of powers set out in the 1947 Constitution. Its decisions—particularly its requirement that the entrenched, powerful members of the original National Assembly stand down and face elections—made Lee’s most ambitious reforms possible. For its efforts, Tom Ginsburg calls Taiwan’s judiciary “an exemplar of the role a constitutional court can play in facilitating democratization.”[xlix] There is no doubt that the Judicial Yuan pushed the limits on some of these cases, especially some of the most controversial ones, but in my view, every one of them was grounded firmly in the constitutional text and/or the Constitution’s fundamental values. I think the court struck the perfect pitch with these decisions: fearless, groundbreaking, thoughtful, legally sound, and written with a presumption in favor of individual liberty as their starting point—everything one could hope for in an independent judiciary committed to the Constitution’s letter and spirit. The public accepted them, and the government honored them.

Third, Taiwan’s Constitution laid the textual groundwork. It is not as comprehensive as other charters we’ve examined, but it has all the ingredients of a modern, effective constitution—including equality under the law, separation of powers (including, importantly, judicial independence), checks and balances, and broad protections for individual rights enshrined expressly in the constitutional text. I find Article 22’s catchall protection of any individual freedoms and rights not harmful to social order or public welfare—what I term the Constitution’s “presumption of liberty”—to be a particularly powerful foundation for enforcing individual rights. Although it’s ambiguous, it sets the tone by making freedom the starting assumption rather than the exception and requires courts to carefully scrutinize any laws that infringe individual liberty. In sum, the Constitution’s carefully enumerated provisions gave, and continue to give, the Judicial Yuan plenty of textual hooks to grab onto when reining in government excesses and building a strong body of constitutional law in Taiwan.

Finally, it would be malpractice to downplay the wave of popular support that spurred the reforms implemented by President Lee and the Judicial Yuan. By the late 1980s, when the government lifted martial law and started the process of democratization, Taiwan had experienced and was experiencing what historians call the “Taiwan Miracle,” a period of rapid industrialization, economic growth, and improvement in living conditions.[l] Increasing public pressure for democratic reforms went hand-in-hand with this growth. As one author put it, by enacting smart, market-oriented economic policies that enabled this growth, the repressive Kuomintang “fell victim to its own success.”[li] As citizens’ prosperity and education grew, they desired more say and engagement in government, businesspersons and professionals sought more economic freedom, and young people grew increasingly resistant to paternalistic authoritarian rule.[lii] Beginning in the late 1970s, activists and ordinary citizens engaged in a series of demonstrations, labor strikes, and civil disobedience to protest the Kuomintang’s power monopoly and press for democratic reforms. This rising public pressure pushed President Chiang Ching-kuo to start the process by lifting martial law and liberalizing restrictions on free speech.

The peaceful public movement for democracy culminated with the Wild Lily student movement in 1990, which coincided with President Lee’s inauguration after an unopposed, one-party election in which only members of the National Assembly voted. For six days, wearing native Formosa lilies as a symbol of democracy, thousands of university students demonstrated in Memorial Square in the capital city in favor of free and direct presidential and parliamentary elections and abolition of the repressive Temporary Provisions. President Lee invited representatives from among the students to meet with him, expressed his support for their demands, and promised to deliver those reforms if they gave him time. Over the next few years, he delivered on those promises. Thus, the driving factor behind Lee’s leadership and the Judicial Yuan’s assertive constitutional rulings was the burgeoning public movement for democracy.[liii] Mentioning the public’s role in Taiwan’s democratization here as the last factor is not meant to minimize it, but rather to emphasize it as the unifying and driving force behind all the other factors.

Scenes from the Wild Lily Student Movement in 1990

Sources: Commonwealth and United Daily News archives, OFTaiwan

Looking forward to other nations, what can we learn from Taiwan’s story? A few things.

First, Taiwan shows that there is no one magic factor that makes constitutionalism possible. Rather, authentic constitutionalism requires at least a degree of cooperation from multiple sectors, Political leadership must commit to it—at very least, Taiwan’s journey could not have happened so quickly and peacefully without President Lee’s remarkable leadership, which produced reforms that often cut against his personal political ambitions. In turn, Lee could not have achieved these reforms so effectively without the Judicial Yuan’s commitment to the 1947 Constitution and its willingness to enforce both the document’s letter and spirit. The Court’s fearless decisions, especially its dismantling of the unelected National Assembly, shattered barriers that Lee might not have overcome on his own, even with strong public support. Further, none of this would have been possible without the support of the public, who drove these reforms at every juncture by keeping the pressure on Taiwan’s political leaders.

Relatedly, Taiwan shows that if conditions are right, the journey from authoritarianism to constitutionalism can happen fast. How many times have we all heard discussion about whether this nation or that nation is "ready for democracy"? I've heard it countless times. This is because we tend to think of democracy as a long process that needs people to think a certain way, that moves along in fits and starts, and that sometimes brings about violence and war. This has perhaps been true for many countries. But others—for example, Taiwan, Spain, and Mongolia—have made the transition rapidly and peacefully. These countries suggest that we aren't thinking about the issue quite correctly. Perhaps we don't need huge cultural shifts among the populace, but rather smaller shifts that need to happen simultaneously. If that happens, the transition can be much smoother and more complete. In a time where democracy and constitutionalism are under attack all over the world, this potential for rapid liberalization is a beacon of hope in a dark era.

Finally, Taiwan shows us that textual ambiguities in a constitution don’t have to doom the whole document. Like Russia’s constitution (which we reviewed in the last installment in this series), Taiwan’s Constitution contains an article that could be used to provide cover for denying most of the individual rights protected in the document. Specifically, Article 23 states that the rights and freedoms protected by the Constitution may not be infringed unless it is “necessary to prevent infringement upon the freedoms of others, to avert an imminent danger, to maintain social order, or to promote public welfare.” Terms like “social order” and “public welfare” are ambiguous and could be interpreted to justify almost any government action. But Taiwan’s government and courts have not exploited this article to give the government free rein to limit individual rights.

I think the difference lies in the baseline assumption: Russia’s government views its constitution as an instrument to give the government legitimacy, and it thus often construes it narrowly or exploits ambiguities and exceptions to deny the rights the constitution claims to protect in order to further the government's plans. But in Taiwan, the Constitutional Court views the Constitution as an end in itself, and it has not allowed the Constitution’s exceptions to swallow its protections and instead has generally adopted Article 22's presumption of liberty as the starting point for its analyses.[liv] Indeed, in several of the Constitutional Court’s landmark decisions, it ruled that government actions or laws violated the spirit of the Constitution and thus undermined it, even where a specific provision didn’t explicitly cover the precise issue at stake. Because of the governmental, judicial, and public culture of constitutionalism, this open-ended provision has not been used to erase enumerated individual rights in practice.

The takeaway here is the same as the observation above: constitutionalism is about more than just the constitutional text. It’s about a nation’s commitment to the constitution in the presidential palace, in the halls of parliament, in the courtroom, in the classroom, and in dining rooms and coffee shops across the country. Taiwan, which demonstrates such commitment in all those places, has evolved into a beacon of freedom in the Pacific.

Liberty Square, which the Kuomintang designed as a shrine to Chiang Kai-shek in the 1970s, became the center of pro-democracy demonstrations in the 1980s and 1990s, and was renamed and rededicated in 2007 as a tribute to freedom and democracy in Taiwan

Kanisorn Pringthongfoo/Shutterstock.com

[i] History, Government Portal of the Republic of China (2022), https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/content_3.php.

[ii] Chris Horton, Taiwan’s Status Is a Geopolitical Absurdity, The Atlantic (July 8, 2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/07/taiwans-status-geopolitical-absurdity/593371/.

[iii] World Population Review, Countries That Recognize Taiwan (2022), https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-taiwan.

[iv] Chien-Liang Lee, The History of Administrative Law in Taiwan Under the Japanese Rule Era (1895-1945): A Neglected Yet Valuable Piece of Legal History for Research, 14 Nat’l Taiwan Univ. L. Rev. 294-301 & n.13 (2019).

[v] Hungdah Chiu, Constitutional Development and Reform in the Republic of China on Taiwan 7 (1993), appearing in Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies No. 2 (1993), https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1114&context=mscas.

[vi] Politics and Diplomacy, Government Portal of the Republic of China (2022), https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/politics.php.

[vii] Han Cheung, Taiwan in Time: The ‘communist rebellion’ finally ends, Taipei Times (Apr. 25, 2021), https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2021/04/25/2003756299.

[viii] Id.

[ix] By Ben Blanchard & Yimou Lee, Taiwan's 'Mr Democracy' Lee Teng-hui championed island, defied China, Reuters (July 30, 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-taiwan-lee-obituary/taiwans-mr-democracy-lee-teng-hui-championed-island-defied-china-idUKKCN24V29C.

[x] Id.

[xi] James Baron, The Glorious Contradictions of Lee Teng-hui, The Diplomat (Aug. 18, 2020), https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/the-glorious-contradictions-of-lee-teng-hui/.

[xii] Tom Ginsburg, Constitutional Courts in East Asia: Understanding Variation, 3 J. Comparative L. 80, 82 (2008).

[xiii] Id. at 83-84.

[xiv] Jiunn-rong Yeh. The Constitution of Taiwan: A Contextual Analysis, 16 Int’l J. Const. L. 702, 702 (2018).

[xv] Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China, Preamble & Art. I.

[xvi] Constitution of the Republic of China, art. 1 (1947) (hereinafter, “1947 Constitution”).

[xvii] Id., preamble.

[xviii] Constitution of the Republic of China, Additional Articles, Preamble (2005) (hereinafter, “Additional Articles”).

[xix] 1947 Constitution, art. 5.

[xx] Id., art. 8.

[xxi] Id. art. 12.

[xxii] Id. art. 15.

[xxiii] Id. art. 17.

[xxiv] Id. art. 21 (emphasis added).

[xxv] Id., art. 111.

[xxvi] Organization Chart, Judicial Yuan, https://www.judicial.gov.tw/en/cp-1668-84500-f8dba-2.html (last visited June 18, 2022).

[xxvii] Preface, Supreme Court, https://tps.judicial.gov.tw/en/cp-1009-34341-f18e5-012.html (last visited June 18, 2022).

[xxviii] Additional Articles, art. 5.

[xxix] Id.

[xxx] Id., art. 4.

[xxxi] Freedom in the World 2022: Taiwan, Freedom House, https://freedomhouse.org/country/taiwan/freedom-world/2022 (last visited June 18, 2022).

[xxxii] Ian Vasquez et al., Cato Inst., Human Freedom Index 2021 at 5 (2021), https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/2022-03/human-freedom-index-2021-updated.pdf.

[xxxiii] Freedom House, supra; Vasquez, supra, at 343.

[xxxiv] Ginsburg, supra, at 83.

[xxxv] Judicial Yuan, 1 Leading Cases of the Taiwan Constitutional Court 9 (2018) (hereinafter, “Leading Cases”) (J.Y. Interpretation No. 261: Terms of Office of the First Congress Members Case).

[xxxvi] Ginsberg, supra, at 83.

[xxxvii] Leading Cases at 15 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 499: Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments Case).

[xxxviii] Id. at 51 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 86: Separation of the Judicial and the Prosecutorial Institutions Case).

[xxxix] J.Y. Interpretation No. 644: Prohibition against Associations Advocating Communism or Secession Case (June 20, 2008), https://www2.judicial.gov.tw/FYDownload/en/p03_01.asp?expno=644.

[xl] Leading Cases at 69 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 445: Prior Restraint on the Freedom of Assembly Case); id. at 103 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 744 (Prior Restraint on Commercial Speech Case).

[xli] Ginsburg, supra, at 84.

[xlii] Leading Cases at 169 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 603: Mandatory Fingerprinting for Identity Cards Case)

[xliii] Id. at 121 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 400: Public Easements on and Taking of Privately-Owned Existing Roads Case); id. at 127 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 440: Taking Without Compensation of the Underground Strata of Private Lands Case)

No. 440 (Taking Without Compensation of the Underground Strata of

Private Lands Case)

[xliv] Id. at 131 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 584: Permanent Disqualification of Taxi Drivers Case); id. at 139 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 749: Temporary Disqualification of Taxi Drivers Case).

[xlv] Id. at 187 (J.Y. Interpretation No. 748: Same-Sex Marriage Case)

[xlvi] See Pew Res. Inst., Support for Same-Sex Marriage at Record High, but Key Segments Remain Opposed (June 8, 2015), https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2015/06/08/support-for-same-sex-marriage-at-record-high-but-key-segments-remain-opposed/.

[xlvii] Chen Chun-hua & Matthew Mazzetta, Same-sex marriage support still up substantially since 2018: survey, Focus Taiwan CNA English News (May 22, 2022), https://focustaiwan.tw/politics/202205220011.

[xlviii] Julia Hollingsworth, Taiwan legalizes same-sex marriage in historic first for Asia, CNN (May 17, 2019), https://www.cnn.com/2019/05/17/asia/taiwan-same-sex-marriage-intl/index.html.

[xlix] Ginsburg, supra, at 84.

[l] Chen Been-lon, Inside the Taiwan Miracle, Taiwan Today (June 1, 2011), https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?post=13965&unit=8.

[li] Thomas B. Gold, State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle 128 (1st ed. 1986).

[lii] Id.

[liii] See, e.g., Chou Hui-ching, From Tiananmen to Wild Lily, Taiwan’s Road to Democracy, CommonWealth Magazine (June 4, 2019), https://medium.com/commonwealth-magazine/from-tiananmen-to-wild-lily-taiwans-road-to-democracy-53d8ed19cfb9.

[liv] Regarding Article 23, Taiwan’s Constitutional Court has adopted the principle of proportionality, which requires laws impacting constitutionally protected liberty to be “necessary,” to be narrowly tailored to minimize harm to the people’s rights, and to demonstrate a tight fit between the means employed by the law and the policy objective sought to be furthered by the government. See Chung-Lin Chen, In Search of a New Approach of Information Privacy Judicial Review: Interpreting No. 603 of Taiwan’s Constitutional Court as a Guide, 20 Ind. Int’l & Comp. L. Rev 21, 26 (2010).